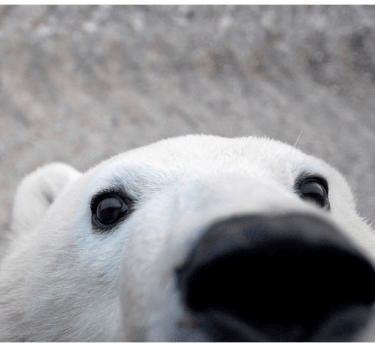

Suppose you are asked to think of a predatory animal. You may imagine a roaring lion, a fearsome bear, or a snarling wolf, likely with their mouths open and teeth flashing within your mind’s eye. One common thing between our image associations with predatory species is the prominence of their canine teeth. Canine teeth are some of the most important tools a predatory animal has at its disposal to capture and feed on prey (since they obviously can’t go to the grocery store or use cutlery!). However, animals also use their canines in social interactions and behavioural displays with other individuals, such as baring their teeth as a defensive behaviour or fighting. Unfortunately, despite their major importance within a predatory animal’s day-to-day life, canines are more likely to break than any other tooth type and are frequently damaged while hunting or fighting. Broken canine teeth are seen in many different predatory animals and polar bears are often found with this kind of dental damage.

Previous studies in Beaufort Sea and Svalbard polar bear subpopulations have found connections between canine breakage and mating behaviours. During the mating season, male polar bears spend most of their time looking for females to mate with throughout their vast sea ice covered environment. However, due to the extended period of time polar bear cubs spend with their mothers, there are often less females available to mate than the number of males looking for love each year. For this reason, male polar bears have to compete with each other for mating opportunities and typically fight during these encounters. As you might imagine, combat between two polar bears is extremely intense and often results in injuries such as broken canines and wounds that are severe enough to eventually scar.

The injuries incurred during romantic pursuits are unfortunate for the bears who receive them but serve as useful tools for researchers because they help us understand aspects of polar bear mating systems and how they may change over time. Western Hudson Bay, one of Canada’s 13 polar bear subpopulations, has been studied since the 1980s which provides high quality data across multiple decades. This subpopulation has experienced a decline in abundance during the 21st century, potentially shifting the proportion of adult females and males in a population from female-biased to male-biased. This possible shift could mean that there are even fewer females available to mate in a given year, creating more competition for male bears which may increase injury occurrences. Our study aimed to understand general patterns of canine breakage and scarring in Western Hudson Bay and examine injury rates over time using 41 years of polar bear data.