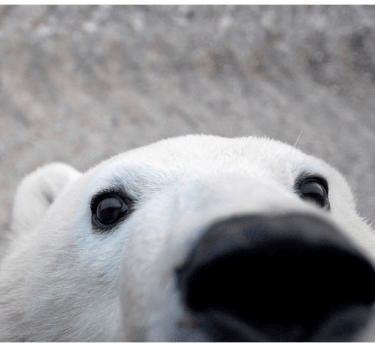

Photo: BJ Kirschhoffer / Polar Bears International

Polar Bears & Land-Based Foods

MINS

16 Aug 2021

"Studies have shown that the calories bears consume on shore do not replace the calories they get from their fat-rich seal diet."

Polar bears in Western Hudson Bay have been forced ashore for increasing lengths of time due to diminished availability of sea ice habitat. When on shore their marine mammal foods are largely unavailable. Longer periods of food deprivation on shore have been linked to declining body stature and survival and to population declines.

Observations of some bears eating eggs of nesting snow geese, and a paper on the topic, have prompted speculation that goose eggs (among other terrestrial sources) could provide an alternate food that might rescue polar bears from global warming. Undoubtedly, some individual polar bears have benefitted and will in the future benefit from consumption of snow-goose eggs and other alternative food sources. But is it probable that such alternate foods are likely to make a difference at the population level?

The paper by Robert Rockwell and others suggests that one seal is energetically equivalent to 88 goose eggs. The average clutch for snow geese is about four eggs, and on average, a polar bear eats a seal about once a week. If a polar bear, stuck on land without access to seals, is going to maintain an energetic position equivalent to the one it had on the sea ice it would need to destroy 22 goose nests each week. If there are about 900 polar bears in the western Hudson Bay populations and they are all on shore searching for goose nests, nearly 20,000 nests would be destroyed each week to support these bears with comparable calories as when on the sea ice.

This of course seems silly in its simplicity. Yet this paper, which some have cited as reason to believe goose eggs might rescue polar bears, concludes that under the most severe predation case, the Cape Churchill snow goose population would decline from nearly 50,000 nesting pairs to fewer than 5,000 in only 25 years. Focused polar bear predation clearly is not sustainable from the goose perspective or that of the polar bear.

Regardless of whether you do a simple calculation or construct complex models, it is clear that the current polar bear population of western Hudson Bay will not be supported by goose eggs. Rockwell and his coauthors, in fact, conclude that predation on snow goose nests may offset some energetic losses polar bears suffer because of reduced time to hunt seals. They do not conclude goose eggs will be the salvation for the polar bear population.

Polar bear biologists have always recognized that some individual bears may benefit from consumption of alternate foods. We have maintained, however, that alternate foods appear unlikely to sustain polar bear populations as we now know them. Studies have shown that polar bears lose about one kilogram of body mass each day they are on land, and that there is no evidence at the population level that they are deriving much sustenance from terrestrial foods. As they come ashore earlier and earlier, polar bears will increasingly search for alternative foods. If, as already shown, all of the existing polar bears were successful in foraging on geese, there soon would be very few geese. Therefore, feeding on geese could be at most a transient salvation, and we have no evidence that other terrestrial foods will be available to supplement the polar bear diet in any meaningful way. More recent studies have further confirmed that most terrestrial sources of nutrition lack the high fat content polar bears are singularly adapted to for survival in a cold climate.

In short, there is little reason to suspect that eating goose eggs or other terrestrial foods will rescue polar bears, and very good reasons to believe that it will not. The only way to preserve polar bears in anything like their current distribution and numbers is to stabilize atmospheric greenhouse gas concentrations so that the necessary sea ice habitats of polar bears are retained.

Photo: Jenny Wong

Meet Our Scientists

With researchers based in the U.S., Canada, Denmark, and Norway, our impact spans the circumpolar Arctic.