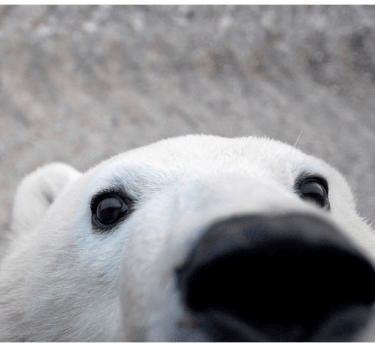

Q: What’s your favorite part about photographing polar bears?

My answer to this question has evolved over the years. There’s the obvious: polar bears are big, beautiful, charismatic megafauna. I’ve always been drawn to their antics and to the “fierce predator” side of them that commands great respect. Every time I’m in the presence of polar bears, I can feel that nine-year-old kid inside of me, bursting with happiness and pride.

I’ve also come to realize that my voice and my photographs are so important in helping to tell the story of the challenges polar bears face as our climate warms and the world they know literally melts away from under their paws. I possess a talent and skill set that enables me to be a voice for the voiceless and I take great pride in that.

I also love the people I get to work with, those who help make photographing polar bears so special. The friendships and bonds I have formed with fellow photographers, scientists, researchers, and guides will last a lifetime.

Spending time in extremely challenging conditions and circumstances, witnessing one of nature’s most magnificent creatures, requires a great deal of teamwork. When you are working and living in tight quarters, dealing with difficult and sometimes dangerous situations, helps you form fast, close bonds—especially when you share a love of polar bears. Wildlife photography isn’t a “one person sport.” It takes a team of people and all kinds of support networks to make these opportunities come to life.

Q: What are some of the challenges of photographing in the Arctic?

Photographing polar bears and the Arctic, in general, provides plenty of challenges: the cost, remoteness, and environmental conditions to name a few. In nature, there are never any guarantees–even less so when it comes to the vastness of the Arctic and the relatively small population of polar bears.

The logistics of operating in the Arctic and working around polar bears are a huge hurdle. To put it simply, you can’t set out and photograph on your own–there are too many potential dangers that lurk, including the bears themselves. To be successful you need at least one other individual, but more often, it takes a team. The Arctic and its climate provide all kinds of hurdles. You not only need to plan ahead, but you also need to have a Plan B and in many cases a Plan C. You must learn to adapt on the fly.

The Arctic’s harsh environment can take a toll on gear and mechanics, and this means being prepared for the worst. It’s not like you can go down the street to the local shop to pick up spare parts or have something fixed on the spot.

In addition, polar bears are one of the world’s largest predators and polar bear safety is not to be taken lightly. As a photographer, you are focused on the task at hand and, if you are alone, you can’t properly be “bear aware,” which means you must rely on others to be your eyes and ears. You must also have proper protection, including carrying deterrents like bear spray as well as your own firearm.

Like polar bears, I prefer cold climates but, in extreme cold, proper clothing is essential. Yet it seems that no matter how advanced the gear gets, one area seems to consistently fall short: gloves. To work the buttons, knobs, and dials efficiently on a camera, you need both warmth and dexterity in a glove. I have yet to find that perfect combination.

The biggest barrier is the cost of photographing in remote locations. As a nine-year-old my weekly allowance didn’t cover those things and that challenge still exists for me. I’m always searching for ways to help fund these expeditions, be it sponsorships, partnerships, private donors, and or outfits that work in the Arctic and require photography.