Photo: Madison Stevens

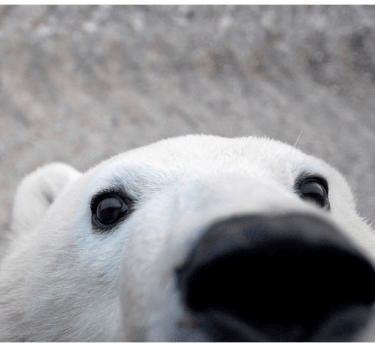

Living with Polar Bears

People in the Arctic have coexisted with polar bears for thousands of years.

Photo: KT Miller

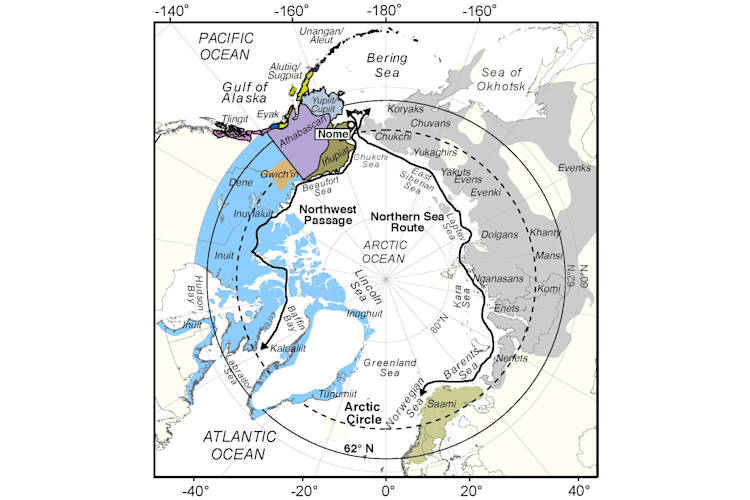

The Circumpolar North

Over 4 million people live in the Arctic today. These include over 40 different ethnic groups of Indigneous peoples, each with their own culture and language. There is a large amount of variability in the cultural, historical, and economic backgrounds across each group.

Northern Indigenous Peoples

The circumpolar Arctic includes 9 nations (Canada, Finland, Greenland, Iceland, Norway, Russia, Sweden, and the U.S.), but polar bears are only found in 5 of these: Canada, Greenland, Norway (Svalbard), Russia, and the U.S. (Alaska).

Four of the so-called “polar bear nations” are also home to Indigenous peoples, each with a unique culture and worldview.

Canada

Home to two-thirds of the world’s polar bears, Arctic and Subarctic Canada has many Indigenous cultures and peoples that have co-existed with polar bears for thousands of years, and continue to co-exist with polar bears today. These indigenous groups include: Inuit, Inuvaluit, Dene, Cree, Gwitch’in, and Metis.

Over 50,000 Inuit live across four regions of northern Canada: Nunavut, Nunavik, Nunatsiavut, and the Inuvialuit Settlement Region. They are collectively known as Inuit Nunangat. Inuktitut is the primary language spoken in this region.

Greenland

The Indigenous people of Greenland include Kalaalitt, Inughuit, and Tunumiit, which share a common identity as Inuit. The majority of the Greenlandic population is Indigenous with over 50,000 Inuit living in the country. Greenland is a self-governing country within the Danish Realm.

United States

People and polar bears coexist along the North Slope of Alaska, the region of coastline north of the Brooks Mountain Range, which spans two seas of the Arctic Ocean: the Chukchi Sea and the Beaufort Sea. This region is the traditional territory of the Inupiat, Alaska’s Inuit population.

Slightly farther south the Gwitch’in and Athabascan peoples also coexist with polar bears, although they live farther from the sea ice and primary polar bear habitat.

Many other Indigenous peoples live in Arctic Alaska outside of the polar bear’s range. These Indigenous groups include the Yuppiit/Cupiit, Eyak, Tlingit, Alutiiq/Sugpiat, and Unangan/Aluet.

Russia

From the Saami inhabiting northern Scandinavia east across Siberia to the Chukokta peninsula, the Russian Arctic is home to many Indigenous peoples who coexist with polar bears today. Indigenous groups along the northern coast of Russia include the Chukchi, Yukaghirs, Yakuts, Evens, Evenki, Ddolgans, Nganasans, Enets, Nenets, and Saami.

Norway

Arctic Norway’s Svalbard archipelago was not a historic home to any particular Indigenous group, and was first discovered by Dutch navigator and Arctic explorer Willem Barentsz in 1596. The northernmost parts of mainland Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Russia are home to the Saami, who are known for their subsistence lifestyle and culture as reindeer herders.

Indigenous Knowledge

Indigenous knowledge (IK) is the English term to define Indigenous ways of knowing. IK is passed down from generation to generation, often through oral methods, and is specific to each community and location—rooted in culture, language, and experience.

IK places a huge emphasis on Land and Land-based experience as a core component of knowing and being.

IK embodies the interrelationship of all things and the concept that how we know something is largely tied to how we came to relate to it, and how we continue in that relationship. IK is more about the journey than the destination and it seeks to know what nature is, not how it works.

IK is currently threatened by colonization and globalization.

Other terms for IK include Traditional knowledge (TK), Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK), Local Ecological Knowledge (LEK), and specific to the Arctic context, Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit (IQ)

Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit

Referred to as IQ, Inuit Quajimajatuqangit is an Inuktitut term that encompasses much more than Indigenous knowledge, but rather “all aspects of traditional Inuit culture including values, world-view, language, social organization, knowledge, life skills, perceptions, and expectations (Wenzel, 2004).”

Inuit created IQ because of their desire to be freed from the narrowness of TEK. The term “traditional” is specifically criticized for placing Inuit knowledge in a historic context, instead of the modern world in which Inuit currently exist.

The use, application, and ongoing existence of IQ is now respected as a way of knowing and is increasingly included and required by governments and universities in research, management, and decision making.

IQ is of particular relevance to polar bears since most of the Indigenous peoples that coexist with polar bears across the circumpolar north share a common Inuit ancestry.

Loss of language, loss of culture, and lack of intergenerational knowledge transfer threaten the ongoing existence of IQ and IK.

Photo: KT Miller

Subsistence Lifestyle

Living off the land is still critically important for Northern Indigenous peoples today. Despite globalization, accessing healthy, nutritious foods in remote communities across the North is incredibly difficult. Food in northern communities is primarily flown in by airplane and is prohibitively expensive.

The Arctic Ocean and ecosystem is like a garden for Northern people, providing affordable and nutritious foods year-round.

A subsistence lifestyle remains vital to Northern life today, and provides important cultural and economic benefits to families and communities.

Photo: KT Miller

Climate Warming

Climate warming doesn’t just impact polar bears and the Arctic ecosystem: it poses a unique threat across Arctic Indigenous peoples and cultures. Common threats caused by climate change include threats to food security, housing and infrastructure, damage from severe weather, and loss of sea ice as a platform for hunting and fishing as well as protection against storm surges.

More than 30 communities are either in the process of, or in need of relocating due erosion from extreme storms. Sea ice historically protected shorelines near communities from erosion, but that is often no longer the case.

Photo: KT Miller